How the integrated model of behaviour helps map barriers and create holistic solutions

Last week I was delighted to contribute to a USAID seminar on how social and behavioural interventions can support efforts to strengthen universal health coverage (UHC). As a briefing co-authored by my ICF colleague Molly Lauria and Kama Garrison notes ‘financial protection programs seek to reduce peoples’ exposure to financial risk, impoverishment, and missed care caused by the need to pay directly for health services… however, a purely economic approach to the interconnected, systemic issues that leave households vulnerable to financial hardship is unlikely, on its own, to lead to UHC’.

The seminar was a useful stimulus to think about how using the integrated model of behaviour (figure 1 below) can help think about the barriers to a behaviour and interventions.

Figure 1: The integrated model of behaviour

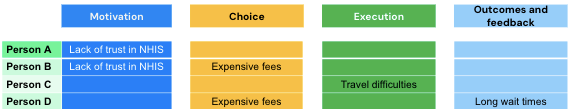

I used an example from the briefing, conditional cash transfers in Ghana, to illustrate this. The scheme provided eligible members of the population with subsidised healthcare but on the condition that they self-enrol each year. Research found that the barriers to self-enrolment include lack of trust in the scheme, concern over health fees, travel difficulties and long wait times for services. These can be categorised using the integrated model and in the table below (table 1), I’ve also illustrated how they might be patterned across individuals (this is hypothetical as I don’t know if this how the barriers were in fact distributed).

Table 1: How barriers to self-enrolment might be distributed across individuals

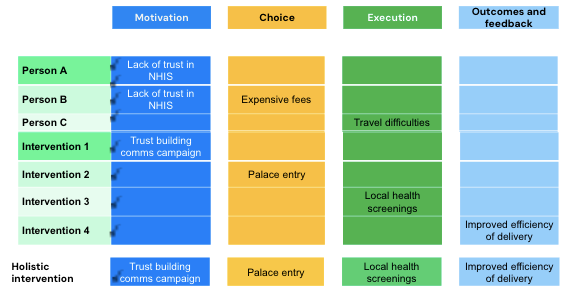

Many behavioural interventions focus on one barrier, and if this were to happen, then as table 2 illustrates it’s probable that the intervention would only have a limited effect. Intervention 1, a trust building campaign, may be effective in changing the behaviour of person A, whose only barrier is lack of trust, but may not be effective in changing the behaviour of person B, who has a lack of trust but also is concerned about expensive fees and is very unlikely to influence the behaviour of people C and D because lack of trust isn’t a barrier for them. Similarly, the other interventions focused on a single barrier are only likely to influence the behaviour of a limited number of people because two out of four of the hypothetical sample of people experience multiple barriers rather than just one. (NB ‘palace entry’ was a way of providing an extra incentive to enrolment as community leaders required proof of enrolment to visit the palace in the city of Goaso.)

Table 2: The potential impact of interventions aimed at one behavioural barrier

In contrast, a holistic approach that combines a range of interventions is more likely to influence a larger proportion of the population, as illustrated in table 3.

Table 3: The potential effect of a holistic approach to behaviour change

This is hypothetical and it’s important to provide the health warning (sic) that although a holistic approach is more likely to be effective with a larger proportion of any given population, that doesn’t mean it will work in reality. That’s why rigorous testing of any behavioural intervention is vital, ideally along with the chance to refine and improve it. However, even this simplified example I think illustrates the potential benefits of an integrated approach in both understanding and mapping barriers and designing holistic solutions.